ON THE LEGACY OF PERCEIVED MENACE

- Details

- Category: Justice

- Published: Thursday, 30 April 2015 19:37

- Written by Pam Keith

by Pam Keith

by Pam Keith

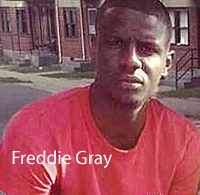

On April 19th Freddy Gray, a 25-year old Black man in Baltimore Maryland, died from an injury he suffered while in police custody that severed 80% of his spinal chord.

We have no idea what happened to cause the injury, but common sense tells us that such injuries do not occur by themselves. In the legal profession, we call it "res ipsa loquitur," or "the thing speaks for itself." Freddy's death was inherently suspicious and in all likelihood the result of reckless behavior. But the real problem is that it was not an isolated incident. It came on the heels of several other incidents in which unarmed Black men died at the hands of police.

In Baltimore, as in Ferguson, Missouri, where Michael Brown lost his life, the community vented its

|

|

|

rage. While random violence is never a productive or intelligent response to pain, frustration, anger and disappointment, it is nevertheless a predictable one. This is particularly so when such emotions are elevated by crowd dynamics. Crowds riot when football teams lose. It should be no surprise that communities riot when they feel enraged by the actions of the government that is tasked with keeping order and protecting them. If order is what the government wants, then those who feel abused will serve up disorder and chaos. It doesn't need to be a rational response, and it certainly isn't when the damage is done to the property of the innocent. But it is a predictable response from those who let loose their pent-up anger and rage.

The question is "why is this all happening?" From one point of view, the young men who have recently died are at least partly to blame because they were not sufficiently deferential to police authority. To some, these men were likely up to no good, and thus suffered the perhaps tragic consequences of their own choices. That point of view, however, is based on a combination of two deeply held beliefs: (a) that police are entitled to absolute deference, and (b) that Black (and brown) men are particularly menacing.

Most Americans believe that police are entitled to respect and deference. But there is quite a difference of opinion as to how that deference must be manifest. Is talking back to an officer unlawful? What about calling a police officer names? What about refusing to follow instructions? At what point does a refusal to cooperate -- or to cooperate fast enough -- rise to the level of actually endangering a police officer? The answer to that question seems to reside exclusively in the subjective point of view of the officer in question. And that is where the issue of perceived menace comes in. An officer is going to respond differently to an angry petite Asian woman than to an angry large Black man. And while we know, theoretically, that both citizens should be treated equally, we also know that they likely won't be.

The perception that Black (and brown) men are especially menacing has been nursed for generations and finds its roots in slavery. Slave owners were ever fearful and vigilant of rebellion and leery of the physical strength of the slaves they owned, which is why they went to extremes to cow their slaves, and most particularly their male slaves. That fear of Black men continued to be perpetuated throughout the legacy of Jim Crow and segregation and simmers still in our society. Our criminal justice system remains permeated with prejudice toward minority offenders, resulting in much higher conviction and incarceration rates and longer sentences.

Regrettably, our young Black men, particularly in urban and blighted communities, have cemented the perception of menace through years of violence perpetrated on each other and on the innocent in their communities. Our young Black men are taught to be tough and to talk tough and they wear that toughness often in an open and conspicuous way. It should surprise no one that those who police our Black urban communities spend an inordinate amount of time with young Black men. Nor should we be surprised that such officers might develop biases and prejudices toward Black men. If 80% of the people a police department arrests are Black men, it should be no shock that the officers in that department would view 80% of young Black men as suspicious: That doesn't make the officers evil, it makes them human.

But the people of this country demand and deserve better than policing by reaction and subconscious (or conscious) prejudice. Especially when such biases are leading to the kind of inexcusable actions that take life. Young Black men should not be paying for disobedience with their lives when no one else in society is. Disobedience should not be a capital offense and police are not imbued with the power to act as judge, jury and executioner. We need reasoned de-escalation of conflict, not escalation or over reaction.

We, therefore, must also have a deep and meaningful discussion about policing techniques. We need to dig into what police officers are taught with respect to the use of lethal force. We need to recognize that all humans are prone to biases and prejudices and develop CONSTANT AND CONTINOUS training to mitigate and reduce the role that such biases play in every-day policing. And we need to embrace the idea of body cameras for police officers, to protect them, the citizenry and most importantly, the fragile trust between the two.

Baltimore burned because a small group of people let loose their rage over the callous disregard shown to Freddy Gray (and many others). I have no doubt that the good citizens of Baltimore will heal from this pain and come together to move forward. The question is "can we all come together to bridge the chasm between law enforcement and the community?" The fact that we are finally having this national conversation is a first and necessary step in the right direction.

|

Pam Keith is running for the office of US Senate and deserves your considerations. http://pamkeithforsenate2016.com/ |